Margaret Lathrop Law: Writer

People still alive recall worldly Miss Law briskly going about Tryon. Widely traveled and keenly observant, she was “born to write.” Articles for newspapers, Saturday Evening Post, House Beautiful, McCall’s and other magazines made her name known around the country. She could write interesting prose about almost any topic. In 1925 she wrote “Collectors’ Pitfalls” for the mass-market Post and “The Glory That is Glass – Past and Present” for more up-market Art and Archaeology. For Travel she did “Sicily’s Vanishing Medieval Peasantry” and “Glamour of Poland’s Countryside.” She authored for national Art News about Philadelphia’s art history. Her thought-provoking 1927 “Legality, Life and Loot” for social-issues weekly The Independent, was about travesties of justice in insurance litigation. Law authored some 1000 non-fiction features published during her lifetime.

Already well-known nationally as a non-fiction writer, Law’s first published verse collection Horizon Smoke was announced to readers of the Tryon Daily Bulletin in its September 29, 1932 edition.

She was born in Spartanburg and spent her first dozen years in South Carolina. In 1902 her banker father moved the family to Philadelphia, where he rose spectacularly to become president of American Bankers Association and head of Penn Mutual Insurance. Among her early articles is one about Charleston, S.C. from where her father’s Adger forebears had come, emerging then from 19th century decline with a renaissance of literary and visual arts. Law’s acquaintance with its “colony” came to influence her writing, especially verse, and ultimately attracted her to settle in the Tryon colony, which had considerable back-and-forth between their creative communities.

Law’s family were cosmopolitan in outlook. For summer vacations they chose seaside Nova Scotia (perhaps using Tryon author Margaret Morley’s guide to it) for sailing, riding and tramping. Margaret became an expert on the province’s arts and crafts, in 1928. Her article “The Hooked Rugs of Nova Scotia” was published in House Beautiful, the influential magazine edited by architect Ethel B. Power in Boston (which published in 1931 a lavish feature on El Taarn in Tryon, the avant-garde Mediterranean-Modernist home of Margaret’s relative Margaret Law Ellertson). That same year, Margaret wrote for it her feature about “T’other End” a unique summer house of Philadelphians at Chester, near where she owned her own cottage at little Hume’s Island in Mahone Bay. In ’37 her House Beautiful non-fiction feature was “Log Rolling in Nova Scotia.” Her 1936 poetry collection Where Wings Are Healed: Songs of Nova Scotia makes Law’s name better-remembered there than in the United States.

Her mother from southern Georgia was ambitious for her daughter’s education and to broaden her horizons. After Margaret’s college graduation, the two went together to Europe. It was to be the first of many such journeys. For brief periods she lived in Sicily, Poland, and France. During the first world war she worked there for American Expeditionary Forces.

Her college was Wellesley, where suffrage-activist Sophie Chantal Hart taught composition and headed its English department. Hart’s eager student Margaret Lathrop Law, Class of 1912, was later named the college’s Alumna Poet. Her master’s degree was in English literature at the University of Pennsylvania. Her deep knowledge of literary form served her in good stead when she took to writing non-fiction features for periodicals serving America’s enormous mass-market for print media during the Twenties. During the Depression of the Thirties she became known, too, as a serious poet. Her verse was published in the likes of Literary Digest, Poetry World, New Humanist and in anthologies. She authored a 1938 essay “But We’re Not All Poets” for The Forum where Henry Goddard Leach, president of Poetry Society of America, counseled writers serious about bettering their poetry. Law bluntly advocates knowing what one’s doing in composition, and to have something meaningful to say.

Second volume of collected verse, 1933

From Gold to Green includes some of her best work. Among her poems is this vivid example:

Scandal Monger

Chic, suave, she offers

A jelly-soft hand.

But her eyes are sharp fish-hooks

Baited to catch evil.

Her mouth, receded in pink lobster flesh,

Is a smoldering volcano

Ready to belch fire and brimstone,

And eat a flame path to the inmost altars of both men and women.

Her soul is shriveled leather, tarred black.

The ruby on her flabby throat

Is a drop of blood drawn from the last victim

Of her slander.

Shortly before the Laws relocated to Philadelphia during Margaret’s youth, the city’s art museum acquired Bonheur’s Barbaro After the Hunt. Later as the museum’s publicist, Law became familiar with the life of its famous painter.

Career Women of America listed her in their directory, a Who’s Who that came out in 1941. In it were many friends. Margaret’s most notable article of 1942 was “Internationalism and Our Children’s Libraries” in Tomorrow, a new journal edited in New York.

At Kennedy Library’s archive in Spartanburg, Law’s unpublished novel Margot exists in manuscript. It’s about Rosa Bonheur, the French 19th century figure who was Europe’s most celebrated woman artist, breaking boundaries and establishing her own independence. Miss Law’s interest undoubtedly was enhanced during her travels in France, where Bonheur’s tumultuous life was far better known than in America.

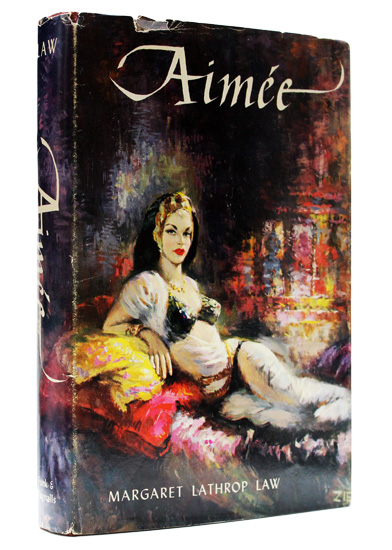

Cover artist George Ziel was born Jerzy Zielezinski in Poland. From the Warsaw ghetto he was sent to Dachau which he survived. After emigrating to New York he was remarkably successful designing book covers for the mass-market, often with depictions of mysterious women in difficult situations.

In 1956 Law’s only published novel came out, Aimée, with striking cover artwork by artist George Ziel. It’s historical fiction about Aimée du Buc de Rivéry, relative of Napoleon’s empress Josephine, an actual 18th century girl lost at sea when she was 14. It was rumored she was captured by Barbary-coast pirates, sold into slavery and bought for Ottoman ruler Abdul Hamid I’s harem in Istanbul. Aimée was thought to have become Naksidil – another authentic historical figure — the Sultan’s favorite concubine, as well as his successor’s mother. When Naksidil died in 1817 the story was popularized (by hear-say testimony from the mother-in-law of France’s ambassador to Istanbul) that the Sultan’s consort had been a French-born woman.

That recent scholarship has debunked the hear-say connection, or that plenty of Fifties novel readers wished the Aimée-to-Naksidil legend to be true, matters not. Margaret’s novel was a hit and it sold well overseas, including in Turkey and in Spanish translation. At age 66, Law’s means were sufficient to allow her comfortable retirement and to reside wherever she wished. She relocated from Manhattan to Tryon. She lived on Vista Terrace within walking distance of the village center.

Portrait for Aimée of author Margaret Lathrop Law.

New York photographer Erich Hartmann photographed

Rachel Carson, Leonard Bernstein, Marcel Marceau

and many other celebrated personalities.

In 1977 she authored an autobiography, now archived in Wellesley College library. Also in their Margaret Lathrop Law trove are audio recordings of Law reciting her poetry, photos and scrapbooks, letters from distinguished people, unpublished books and short stories, and such juicy materials to browse as a box of 1936 correspondence labeled “Ego-inflating letters as counter-acting rejections.”

She died in Tryon in 1988 at the age of 98.

This writer is one of four women who, at one time or another, were in Tryon and went by “Margaret Law.” Their identities are often confused.

Law’s 1939 collection gathers her poems

about the South.

Its cover image Woman Hoeing

was one made well-known

by her aunt,

visual artist Margaret Moffett Law.

Her aunt, Margaret Moffett Law (1871 – 1956) is well-remembered in art history, especially for her Modernist prints and paintings of Black people. She painted in France as well. Born in Spartanburg, she attended Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. During the Twenties she taught art in Baltimore. Miss Law returned to live in South Carolina in 1936. Her North Carolina mountain cottage was at Lake Summit. Both aunt Margaret M. Law and writer Margaret L. Law are buried in Spartanburg, S.C.

The visual artist’s brother, and thus the writer’s uncle, was entrepreneur Andrew Moffett Law (1877 – 1956) buried in Tryon Cemetery. His wife (the writer’s aunt-by-marriage) was Margaret Adger Williams Law (1884 – 1961) born in Charleston, buried in Tryon Cemetery too. The couple’s prominence in Tryon helped to make its people keenly aware of what Margaret Law the Writer was publishing from Philadelphia, and later New York, and to “talk her up” among their acquaintances elsewhere in the nation.

Their daughter Margaret Williams Law (1907 -1979) is buried in Tryon Cemetery. She studied art in New York but wasn’t active as a professional artist. Her first husband was Tryon artist Homer Ellertson (1892 – 1935) a native of Wisconsin. Her second husband was Tryon architect Arthur Laidler Jones II (1897 - 1961) from Charleston. (His mother Elizabeth Warren Jones was well-known as a Charleston Renaissance poet — frequenting Tryon as well — related to writer Margaret Lathrop Law only distantly by her son’s marriage.)

Michael McCue

August 29, 2023