Rock House Gallery

photos by Brooke Sanders

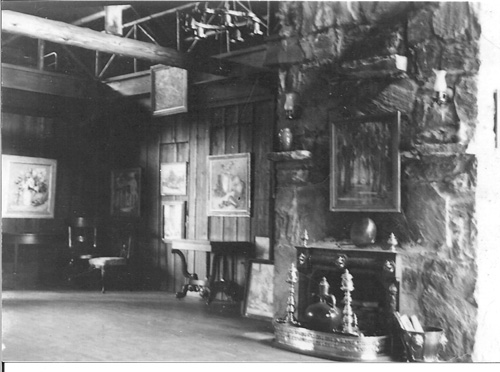

By the time cosmopolitan painter Josephine Sibley Couper (1867 – 1957) opened her Rock House Gallery in 1933, Tryon was already a well-known artists colony. For forty years it had been attracting writers, dramatists, musicians and visual artists from around the nation. Painters exhibited at The Lanier Club, the Episcopal Parish House, and at commercial galleries in New York, Chicago and other major cities. In Tryon artists often sold work out of their own studios, or in the homes of friends who held “showings” of fresh paintings at private events by-invitation. The Rock House was North Carolina’s first commercial gallery for contemporary art.

Recent owners have added an elevated koi pool. This rustic bench structure conceals its recirculation pump.

Searles often designed quirky windows, as this arrangement in the loft gable.

Doors from Couper’s studio to main room have viewing grills which may be closed to prying eyes, from inside the studio, by little sliding screens.

Couper acquired a picturesque stone-and-log building designed by Tryon architect John Foster Searles in the 1920s to serve as sales office for the ambitious Blue Ridge Forest resort on nearby Hogback Mountain. It is across from the train depot, within sight of Trade Street, the busy artery that by the ‘30s was bringing thousands of automobile tourists from South Carolina into the scenic mountains on a paved highway. Adjacent to her gallery was Oak Hall Hotel, where authors Thomas Wolfe and F. Scott Fitzgerald had their last face-to-face encounter.

Couper’s painting studio was at The Rock House, for her landscapes and portraits. In her exhibition space, she showed the likes of artist Charles Aiken (1872 – 1965), member of New York’s Salmagundi artists club and founder of The Fifteen Gallery in Manhattan. Her own New York gallery was the Milch; she exhibited often in Charleston, S.C. and was close to many artists of the Charleston Renaissance art movement. In Tryon she taught women artists privately at Rock House, and hosted overnight her visiting friends and her children from out of state.

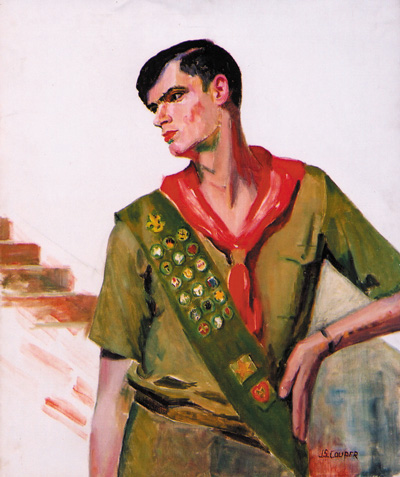

One of her local informal portrait models, Holland Brady (whose unfinished portrait in his Boy Scout uniform is shown here), recalled Couper as grande dame reigning over Pacolet Street from the Rock House verandah. Impeccably attired and wearing white gloves, the regal Mrs. Couper would nod, raise her gold-knobbed walking stick, or speak to acknowledge passers-by according to their age, their rank, and her favor.

self portrait circa 1935

Oil on canvas 24 x 20 in.

courtesy Museum of Arts & Sciences, Macon GA

There was no doubt she was wealthy and well-connected, and cultivated her Georgia upbringing as her persona. Yet her father Josiah Sibley came from Massachusetts to Augusta before the Civil War, where he made vast fortunes both before and after. He was an abolitionist who freed his slaves, educated them for trades, and financed their commercial establishment in Liberia for those wishing to return to Africa. At twelve Josephine made her first tour to Europe with her family. The magnificence of its art made a great impression. She let it be known she wanted art lessons so an instructor was engaged, and after that she never stopped sketching and painting. At 18 she was studying with a friend of John Singer Sargent, fresh from Paris. Josiah built a studio for her on the grounds of the Sibley mansion, and had the roof torn open for an attic studio at their country retreat as well.

In 1886 she enrolled in a Charleston art academy, but soon announced her desire to venture on to New York. Couper studied at Art Students League and then with William Merritt Chase, famous mentor of many important women artists, who was highly supportive of her talent. Her station and scruples, however, kept her from attending a class scheduled for 7 p.m. because she felt no proper lady could be on streets unescorted in the evening. In 1890 she went to Europe, ever-ambitious to become one of America’s foremost painters.

The next year she married Butler King Couper, a cotton broker, who first worked in Atlanta and later in Spartanburg, S.C. In that growing city not far from Tryon she helped to found its Arts and Crafts Club, and studied under painter Elliott Daingerfield from Blowing Rock in the North Carolina mountains, who introduced her to people at Tryon. He taught at Philadelphia’s School of Design for Women from 1895 through 1915. Some of the Tryon women who also were active in Philadelphia art circles during that period were Amelia Watson (a Connecticut native), Margaret Law (sister of a businessman who divided his time between Spartanburg and Tryon), and Amelia Van Buren (from Detroit, who eventually settled in Tryon and there sold her famous portrait by Thomas Eakins, now one of the crown jewels of the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C.)

Couper’s husband died in 1913 and after their children matured she moved in 1922 to Montreat near Asheville, summering in Gloucester, Massachusetts – an important colony where other Tryon artists congregated too. Painters there were heavily influenced by Modernist trends, so in 1929 and ’30 Couper went to France for work with André Lhote, a theoretician who credited Impressionism with having begun the Cubist rejection of visual reality. He pushed her to experiment with abstraction and one of her canvases was shown at the Salon d’Automne in Paris.

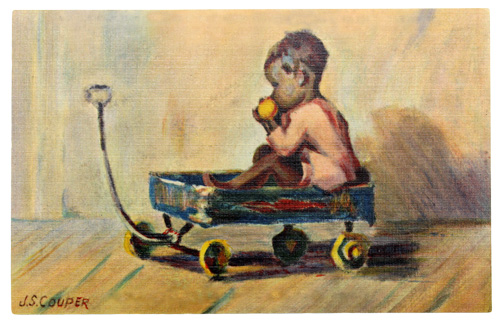

American opinion leaders’ attitudes about the nature of art and about black people were changing radically at the time. Couper’s sympathetic genre study of a black child in a toy wagon was exhibited at the National Arts Club in New York. Despite her privileged background, she became interested in the cause of unwed mothers and supported – with her personal donations -- less-judgmental social justice for them. Even as her personal perspectives were changing, Couper had five one-man shows in Manhattan, and a solo exhibition at Atlanta’s High Museum.

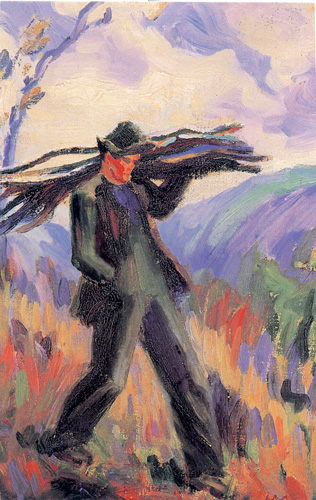

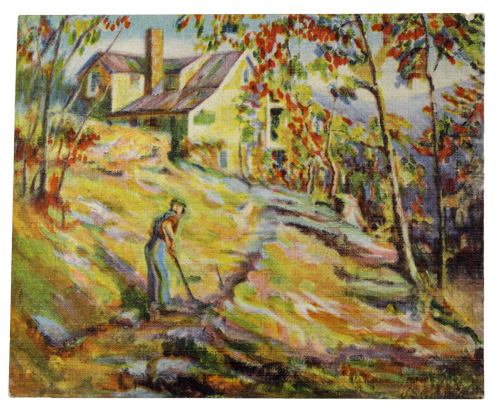

In the Blue Ridge Mountains is Couper’s painting depicted on the cover of the Oct. 31, 1931 issue of influential magazine Literary Digest.

By the start of the Second World War she was already in her seventies. She already had paintings in the collections of good museums, portrait commissions had dried up for every artist, and leisure travel through Tryon declined greatly during the war. Couper recognized the inevitable. Blue Ridge Weavers, retailers of arts and crafts nearby on Trade Street, was where she consigned some reasonably-priced “gifty” sketches. Oak Hall Hotel exhibited some of her unsold canvases to brighten things up there. Her gallery kept short and infrequent hours, and Couper spent much of her time traveling, while offering apartment rentals at The Rock House. When in town, she socialized and supported local good causes. Her last really innovative project was a “street show” after war’s end, in cooperation with seven Trade Street shops (including a food retailer) doing show-window merchandising for 1945 Christmas season. Couper’s paintings were, essentially, not displayed as Fine Art but as graphic-design thematic props. Ironically the 20th century art world concluded with graphic tropes ascending into High Art, with well-heeled museums collecting Campbell’s Soup Can images by Andy Warhol.