Tryon as Traumfest in 1913

Down-North and Up Along, her 1900 account of Nova Scotia, was Margaret Warner Morley’s first success authoring a travelogue for adults. Published by Dodd, Mead & Co. in New York, its breezy language and sense of humor invited adventurous Americans to experience a region known to relatively few. The book’s great appeal derives from describing joys of intimate, personal “discoveries” away from vacationing crowds. At that time a “tourist” was an independent, intelligent traveler seeking the less-traveled route, finding comfort and meaning among distant strangers who turn out to be, after all, remarkably like ourselves.

Following on her next remarkable success – writing a romantic travelogue of the Italian Alps, Donkey John of the Toy Valley, finished at her Tryon home in 1909 – Houghton Mifflin publishers of Boston and New York contracted for an even more ambitious travelogue. Western North Carolina’s mountains were by then a booming region for “new tourism” – independent travel by American motorists well-off enough to explore in their own “touring cars” – or to arrive by train, then to tour on foot, to rent riding horses or to hire a horse-drawn vehicle, or even to rent an automobile, a new opportunity.

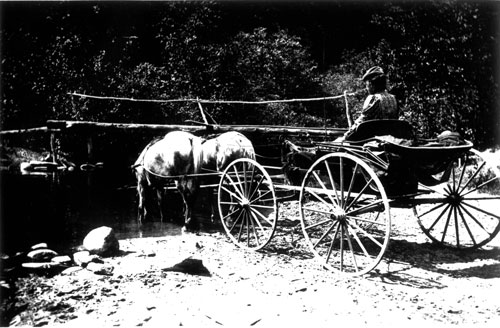

Miss Morley waits at the ford, while Dan and Tom drink

Morley’s The Carolina Mountains hit the market in October of 1913. It was an instant success. Her informal, tongue-in-cheek accounts of a cosmopolite’s impressions were informed by her intimate acquaintance with the region, for some twenty years, often exploring on foot. She was, as well, a capable buggy-driver through rough terrain.

Describing her own base of operations, Tryon village, in the book she chooses to call it Traumfest for literary purposes. “Tryon” doesn’t even appear in its index, although Tryon Mountain has a number of entries. The writer’s decision has confounded many readers and scholars for more than a century. A nom de plume for an author is common; a nom de plume for an actual locale is rare except in fiction or fantasy.

Traumfest lies in a nook of the Blue Ridge Mountains, and although it may not appear by that name on the maps, the place itself is a reality. The enfolding mountains, so dreamy, so enchanting in coloring when seen at their best moments, will explain the name and justify it, for translated into English “Traumfest” means “Holiday of Dreams,” or, if one is willing to tamper a little with grammatical endings, it means, best of all, perhaps, “Fortress of Dreams.” Here lingers a touch of summer even in midwinter, because of the evergreen trees and shrubs that so abound. And here spring comes early, for Traumfest, be it known, lies in the thermal belt, that magic zone where, although it may freeze, there is never any frost . . .

The peculiar charm of Traumfest comes from the fact that it lies thus open to the east . . . In the dewy morning one sees the sky lighten, and then the torch of the day flash from hill-crest to hill-crest, the tree-tops kindling in masses, with night shadows yet intervening . . .

Because of its warm and beautiful location, and because the railroad came through that open door of the mountains, passing up the Pacolet and over the crest of the Blue Ridge to Asheville, Traumfest is not only the largest of the villages on the eastern slope of the Blue Ridge, but was among the first to become a resort for visitors from all parts of the country, here having grown up a friendly community representing more than two dozen states. Strangers say that Traumfest reminds them of an Old World village, with its bright painted houses and the little church with its square stone tower . . . Traumfest seems to have happened, straggling about over a number of ridges separated from each other by deep hollows through which pass connecting roads, or down which run dancing brooks. It is all up and down hill, most of the houses having their front door on the hilltop and the back door down below somewhere. It adds to the unstudied effect of the place that houses are set at every angle . . .

Although Traumfest now contains enough new settlers considerably to temper the manner of life, its ancient quality is not all gone, as he who tries to get anything done on time, or done at all, will soon discover. That ox team slowly pulling a load of wood along Traumfest’s main residence street . . . Traumfest’s main street is bright red . . . composed largely of red clay . . . here and there you will see a stream flowing with blood-red water. Men and boys have red ends to their trousers, horses have red hoofs and white mules have bright red legs . . .

Traumfest has a spice of border romance . . . that picturesque figure the “moonshiner,” who persists in distilling corn whiskey in secret places and in passing the cup that cheers and most certainly inebriates, in defiance of the laws that declare such to be unlawful. [North Carolina voted for statewide Prohibition in 1908, a full decade before national Prohibition. Morley authored an article for Boston’s influential Evening Transcript which argued sympathy for moonshiners. In fact her own grandfather Isaac Morley had been involved with the distilling business in the Pocono mountains of Pennsylvania.]

That the sun in time conquers even the most vigorous newcomer is a fact discernible in Traumfest, where people may be divided into three classes: Northerners who are always in a hurry, Southerners who are never in a hurry, and Northerners in process of southernization, who are sometimes but not always in a hurry. In course of time the Northern type becomes obliterated unless renewed from the original source . . .

Besides the white people, Traumfest is blessed with the negro . . . They are good, and for the most part as industrious at least as the white people, and when you know them personally and intimately, you cannot help loving them. [And here Morley launches vivid word-pictures depicting stereotypes of her era. From its founding, Tryon’s population included black people who worked for the railroad, in the vineyards, as domestics and in services, teachers and entrepreneurs. She doesn’t portray, say, the headmaster of the Episcopal Colored School who constructed a hilltop manse much more impressive than her own modest abode. Indeed, next door to Miss Morley and Miss Snow’s cottage on Melrose Avenue, Edmund Embury from New Jersey was then tutoring black children at his home.]

Grove Park Inn, which opened the same year as the publication of The Carolina Mountains, commissioned a special edition of Morley’s book, to place one in each guest room along with the Bible. Thousands of guests bought their own souvenir copies bound in buckram from the hotel gift shop. The author of this essay owns a copy that belonged to Melville Dewey, inventor of the Dewey Decimal System for libraries.

About Traumfest the blackberry has a rival in the Japanese honeysuckle, that, having escaped from the gardens, densely covers banks and open places. Red clay evidently suits it. It buries a stone wall or a fence in a year or two, blossoms tremendously, and loads the air with its delicious perfume . . .

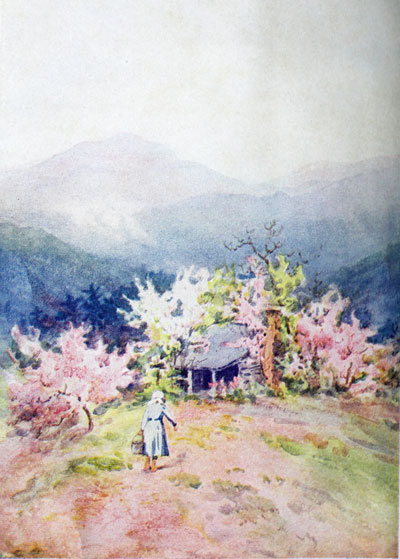

Early flowers are only the prelude in the floral drama that reaches climax when the mountain laurel, the flame-colored azaleas, and the rhododendrons come . . . when driving up a certain mountain near Traumfest, one sees the snowy drifts of dogwood through a veil of bright red-bud in misty ravines; that mountain from whose side one looks down to where beyond the hills the lowlands spread, reaching like a summer sea to the far horizon . . .

frontispiece for The Carolina Mountains 1913 reproducing a watercolor by Amelia M. Watson, the Connecticut artist with whom Morley first wintered at Tryon at playwright William Gillette’s retreat “Thousand Pines” in 1891.

When [azalea] are in bloom, we visit the Warriors for certain hollows, we go up Tryon Mountain, we frequent wild heights of Hogback and Rocky Spur. We warm our senses for a month in the fire of flowers [and Morley continues, describing the entire mountain region enveloped with flowers on a massive scale, teasing readers to come see for themselves whether it’s true. During this era, sophisticated novelist Claude Washburn deployed the motif in his novel The Green Arch, where Tryon village is called Beckett. In Washburn’s tale, a cosmopolite escapes the normal world by taking his horse under a massive rhododendron on Tryon Mountain to enter an enchanted land.]

In the higher mountains there are no mosquitoes, and there used to be none at Traumfest in those good old days before the stranger had begun to “improve” the place. Summers of Traumfest are sweet beyond words to express and the thermometer goes no higher here than in the North – not so high very often – and the nights are cool; but hot season lasts longer, so those accustomed to five or six weeks of midsummer heat sometimes grumble when they get four months of it. But no one who has not spent a summer here can hope to know what these woods are capable of in the way of sweet smells . . .

1891 specimen of perfect Perry strawberry grown by George E. Morton, Tryon City N.C. Library of Congress

About Traumfest plums, peaches, peaches, peaches, berries, the most delicious of grapes – Traumfest is noted for its grapes – apples – such as they are – figs – and melons! Wagonloads of watermelons stand about waiting, not in van, for customers . . . If you look over those fields where great blue passion-flowers bloomed all summer, you will see leathery-skinned fruits as large as a goose egg lying about by the basketful. These are maypops. If you break open a thoroughly ripe one, you will be assailed by an aroma that makes you think of tropical fruits, of perfumed bowers, of Arabian Nights banquets, of fair gardens, and strange tropical flowers.

Inside the maypop resembles a pomegranate, but the patrician pomegranate has no such heavenly flavor as has the wild and worthless maypop. What our fruit-makers are thinking of not to cultivate it, one cannot imagine. It offers possibilities that ought to tempt them behind the power of resistance. In some parts of the mountains people call maypop “apricots’ and eat them, though they belong principally to the age of childhood. These strange, exquisite, good-for-nothing fruits are product of the passion-flower vine. Later than the cultivated grapes, about the time of maypops, come wild grapes, among them large sweet muscadines that country children bring in by the bushel . . .

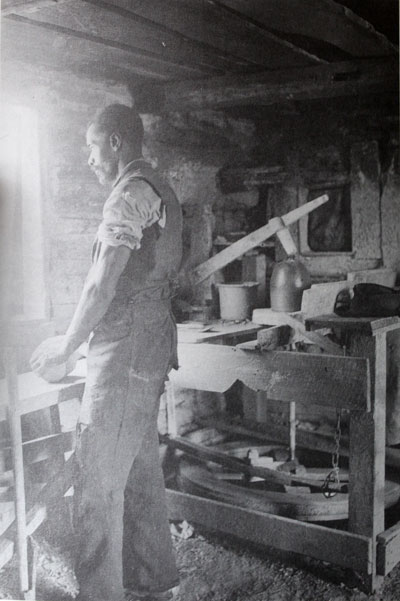

Rich Williams, potter at work, photograph by Margaret Warner Morley

It was while at Traumfest one was fired with ambition to discover the maker of rude but picturesque jugs in such general use there . . . below the mountains at Gowansville, some ten miles from Traumfest. He is an old-time negro, as black as ebony, evidently very proud of your visit, and you are soon watching hands knead clay and pat it into a loaf, then on the wheel coax it into shape. Veins stand out like cords on Rich’s sinewy arms, his long hands draw the clay loaf up, up, into the stately two-gallon jug with its narrow mouth, or into the wide-mouthed butter crock, or the pug-nosed pitcher, big or little. Rich loves his work. Looking at him, you seem to see before you the original potter. His wheel, which looks as though he had made it himself, is in a little log hut, lighted by one tiny window. He digs clay from the bank of Tiger River that runs near – slate-colored, adhesive clay Rich says is “powerful good” for jugmaking. He grinds it in a wooden box by the help of a slow-footed mule that walks in a circle at the end of a long curved beam which turns an upright shaft fitted with wooden teeth at its lower end . . .

Rich tells you his glaze is made from ashes and clay, that he washes jugs inside and outside with it, and then sets them in the oven, a long low vault with a fire-hole at one end. He sets in his jugs, makes up a wood fire, and bakes them until they are done . . . Rich’s jugs are homely, but one likes them, they are so honest. A jug made by a potter who dug the clay out of the bank with his own hands, and soaked it, and ground it, and shaped it, and glazed it, and baked it, must be a wholesome sort of jug to have in any house. We had formed the habit of setting groups of Rich’s jugs in the fireplace, partly to heat the water, and partly for the picturesque effect, long before we knew of the ebony hands that moulded them out of clay of Tiger River. . .

The Holiday of Dreams

Back to Traumfest one comes, after each expedition out over the mountains. And one day truth dawns upon you – the title so arbitrarily bestowed upon Tramfest belongs to the whole region. Yes, this whole stretch of enchanted mountains is the “Holiday of Dreams.” And thinking back over those days of happy wandering, how many interesting places appear before the mind’s eye that have not been so much as mentioned in this book; how many lovely scenes witnessed, how many pleasant adventures encountered not recorded, how many birds have sung unchronicled, how many quaint native phrases have been passed over in silence!

And as years have slipped by, with what pangs of regret one has watched passing of primitive life, and what pleasure one reverts to to days when everybody was uncomfortable and everybody happy. How many today, seeing the train with Pullman sleepers come in at Traumfest, the conductor politely stopping his cars on request of any lady passenger who wished to gather a few wild flowers . . . like a cosmic spider, Southern Railroad has woven its meshes below the Carolina mountains on either side, while now yet another line is being surveyed across the Blue Ridge to the north of Tryon Mountain, up Broad River Valley past Chimney Rock, and on as far as Bat Cave . . . [this new rail route proposed when Morley wrote was never constructed].

And what means that sudden appearance of two dozen automobiles on Traumfest’s modest Trade Street the other day. Two or three of these wonders belong to people living here, and those others came on a mission which was to further their own interests by making plans for extension of the road that brought them here. They came up from Spartanburg, a sign of the new era dawned to transform the mountains. For already comes a wide, new road, a great red serpent whose head is pointed up Pacolet Valley, and that will never stop until it has coiled and writhed its way over the helpless rampart of the Blue Ridge to its goal – in Asheville? No, not in Asheville, but through it and on and down into the new teeming Western world beyond . . . Wherever you go the portable sawmill is ahead of you, the temporary railway of the lumberman disdainfully penetrating “inaccessible” places . . . The comforts that are pouring in are not in themselves regrettable; it is only the price one has to pay for them, the exchange of Arcadia for Gotham.

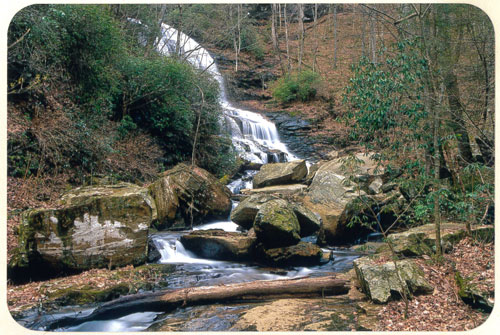

Pearson's Falls courtesy Beth Rounds

Morley writes on to plead, and to hope for, an Appalachian National Park to save some Carolina wilderness she loved. A native of Gotham, also known as New York City, Miss Morley didn’t live to see that happen in the 1930s. While still a writer resident of Boston, she joined its Appalachian Mountain Club, founded there in 1876 for hiking and for nature preservation. Miss Morley died in Washington D.C. in 1923. In 1931 alarmed Tryon residents saved one of her favorite haunts, Pearson’s Falls Glen outstanding for botanic richness, from purchase for clear-cutting. It remains some 250 acres of managed virgin forest, owned and maintained by Tryon Garden Club, the nation’s first preserve specifically dedicated to maintaining species diversity.

Michael McCue

April 2023